|

stonemasons, operative masons, speculative freemasons |

||

|

|

||

|

|

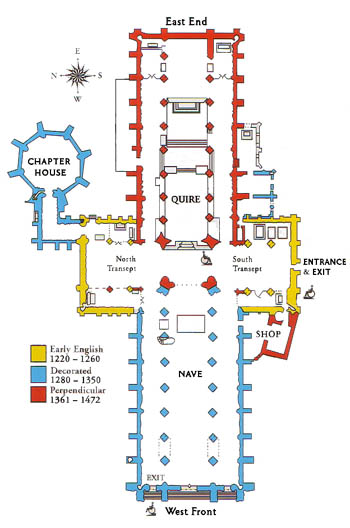

york minster floor plan Stonemasons and Operative Masonry Today Summary Stonemasonry continues to be practiced today much as it was in the early days of Freemasonry, as demonstrated on a recent research trip to York Minster to talk with the stoneworkers there. Much like their predecessors, they were actively engaged in shaping and replacing damaged stones in the ancient cathedral, yet they took some time to talk about their work. Several striking images of stone- cutting in progress enhanced this experience. The early relationship between stonemasons and Freemasons has been extensively discussed and debated. Yet there is no doubt that there has always been a significant amount of respect and admiration for the men who shaped stones with their hands and built the world’s cathedrals and other inspiring structures. It is reassuring to know that these stonemasons are still active and working among us. For clarity, it should be noted that stonemasons carved rough-hewn stones into carefully designed blocks of different sizes and shapes to build the castles, mansions and bridges in remote places, as well as the cathedrals, townhouses and smaller churches in the cities. On the other hand, Freemasons have used the tools and practices of stonemasons as symbols of how to live a better life, while developing bonds of brotherhood and mutual support in private meetings and activities. By custom, since stonemasons actually operated the tools of the craft, they are now familiarly known as “operative masons.” As Freemasons reflected on the work of stonemasons, but did not personally hew stones, they have become known as “speculative masons.” With the general collapse of stonemasons’ lodges in the late 1600’s throughout England and Scotland,[i] the concept of operative lodges largely disappeared. Without those guiding centers, stonemasons basically became employees working alongside carpenters, glaziers and others at the convenience of owners or the owners’ representatives. Their operative lodges disappeared almost everywhere except at cathedrals or similar massive sites where ongoing repairs or additions necessitated a virtually permanent lodge. Regretfully, these sites did not have the freedom of the independent stonemasons’ lodges, where they could choose their own projects and enforce their own rules. The lodges at cathedrals, today as in the past, were kept for the convenience of the religious clergy, who gathered together as a Chapter, and set out the rules and guidelines for the lodge at their location. Yet the stonemasons' work has persisted. Due largely to the need to repair and restore ancient buildings raised with stone, they still carve stones today, some cut from the same quarries as in days of old. They use the same mallet and chisel, square and rule, that were used in antiquity. This was clearly the case at York Minster in 2008 when I talked with stonemasons still plying their trade after all these years, and learned about the challenges and tremendous satisfaction associated with their work. On site, Master Mason John David oversaw the work being performed, and was especially helpful in explaining the current state of their craft. The challenges faced by these stonemasons included the sheer immensity of their cathedral, with countless thousands of individual blocks making up the massive Minster in York. Each stone had its own individual shape due to the space available, the structural load which needed to be supported, and the artistry of the piece. Many pieces, especially on the outside of the Minster, became so eroded that the design, human face, gargoyle, or fluting which adorned it was partially missing. For these, the Master Mason would examine all the surrounding stones to find those similar in design, and then craft a full-size model of how the replacement stone was to appear. From that model, the apprentices and fellowcrafts would carefully carve an exact duplicate in stone. Much the same process had been followed in the original construction, with the added requirement of basic design. One of the most impressive elements of the construction of our great cathedrals and our small parish churches, is that they were “designed” and set out using only three tools, a straight edge, compasses and a square. Using these tools it is possible to create regular and irregular polygons. A fifteenth century account gives instructions on how to draw shapes, up to a dodecagon, to create arches of varying curve, and to find the centre point of an arc. All of these practices could be taught without the need for specialised mathematical knowledge. It would appear that these geometric “secrets” were handed down through the generations by word of mouth, experience and practice.[ii],[iii] Square, compass and rule have continued to be used in this work. In addition, forms cut from sheet metal have been used which exactly matched each interface between the particular stone being replaced and the ones around it. The match had to be exact, because the surrounding stones could not be changed. When the work on each intricately carved stone was complete, the Master Mason examined it against the model and the old, damaged piece. If it was found to be a perfect match, a Mason’s mark was carved onto one face of the stone which would not be visible to the public after it was installed. No stone could be placed into the Minster without the Mason’s mark. The object of all this work was to replace broken or eroded stones with solid pieces which exactly matched the load-bearing ability and design of its predecessor. If the work was done correctly, each person entering the awe-inspiring cathedral, with its vaulting arches and intricate designs would never notice the replaced pieces. The visitor would only experience the same feelings which filled people when they first walked through the Minster 770 years ago. And if the work was done well, people would still be able to walk into this cathedral 770 years from now. The York Masonic Hall stands in direct view of the Minster. It is easy to find, with the large words “AUDI, VIDE, TACE” inscribed above the upper windows. These words mean “Hear, See, and Be Silent,” and are also found on the coat of arms of the United Grand Lodge of England. I was courteously invited in and made conversant with aspects of the long history of the Lodge and Hall by Bro. David Hughes. Notes: This article is by Sanford Holst. First published online October 23, 2008, at www.MasonicSourcebook.com. Photos © 2008 by Sanford Holst, but may be used if permission is requested and granted: email sourcebook editor. [i]

Harry Carr “Freemasonry Before Grand Lodge” in Grand Lodge

1717-1967 (Oxford: United Grand Lodge of England, 1967), pp. 36-41. [ii]

The Dean & Chapter of York How Was It Done? (York, 2006), p.

6. [iii]

Peter Hill and John C.E. David Practical Stone Masonry

(Shaftesbury, UK: Donhead, 1995).

York Minster Floor Plan

________________________________________________________ Rare Masonic books, Civil War, Best Masonic books, Masonic directory, Masons Templars, Masonic research Masonic authors, Civil War2, Templar medals, Table Lodge Buffalo Bill Cody, Quarry Project, Old Time Freemasonry Sworn in Secret, Early American, Knights Templar, Civil War3 Latest books, Born in Blood, Solomon's Temple, Coil's Encyclopedia York Rite, Allen Roberts, John Robinson, 2010 symposium, Allen Price Grand Lodge England, Holy Grail, Kabbalah, Nadia, Robert Burns Masonic education, UCLA, Stonemasons, Scottish Lodge US Lodges, UK Lodges, Canada Lodges, Australia Lodges Templar Swords, Freemason, Templar Trials, Templars Vatican Origin of Freemasonry, Templar history, Freemasons history © 2008-2024 Sanford Holst - web design by webwizards |

York Minster

Raw Stones

Carving the stone Model (left) and carved stone (right)

York Masonic Hall and Lodge

-

|